Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a hyperkinetic movement disorder that can arise in patients taking antipsychotics or other dopamine receptor blocking agents and significantly impacts their lives.1,2 As a result, it is critical to identify, accurately diagnose, and appropriately treat TD that has an impact on the patient.1,3

TD is a typically irreversible hyperkinetic movement disorder resulting from chronic exposure to typical and atypical antipsychotics or other dopamine receptor blocking agents (eg, antiemetics, prokinetics).1,4-7 TD can impact patients’ lives and undermine the stability of their underlying mental health condition.2,8 As a result, expert consensus recommends that patients taking antipsychotics be screened for movements at every visit regardless of the risk of TD.9

Abnormal movements in TD can affect any part of the body, but most often impact the face, causing lip puckering, grimacing, and tongue protrusion. Movements are also often seen in the trunk and limbs.1 Screening can be conducted unobtrusively as patients enter the consultation room and engage in conversation.10 Clinicians can also empower their entire office staff to be aware of these movements, recognize them in patients, and report observations to the provider. Because patients can temporarily mask the movements of TD, it may be necessary to employ activation maneuvers to uncover them (Video 1).10,11

Patient images used with permission.

Effective management includes using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) exam to make careful examination of movements affecting various body regions and asking detailed questions to understand the impact of movements and the severity experienced by patients.3,8,12 Since patients might not be fully aware of their movements or the effects they have, it may be helpful to seek feedback from caregivers regarding any abnormal movements.8

Drug-induced movement disorders (DIMDs) include TD, drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP), akathisia, and dystonia.13 Historically, these disorders were all classified as “extrapyramidal symptoms” or EPS, a now-outdated classification that misdirects the need for a specific diagnosis.1,13-15 DIMDs have distinct pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical manifestations, necessitating different treatment approaches.1,13,16 It is critical that TD is differentiated from DIP since treatment for one can worsen the other.16,17

TD and DIP are different disorders with different causes (Video 2).1,16

- DIP is a hypodopaminergic state: the acute blockade of dopamine receptors caused by some antipsychotics leads to a reduction in postsynaptic dopamine signaling. Reduced signaling results in decreased movement and other symptoms associated with DIP.15,16

- TD is a hyperdopaminergic state: it is thought that chronic blockade of dopamine receptors results in the upregulation of dopamine receptor function. This is possibly due in part to hypersensitivity or upregulation of dopamine receptors. This upregulation results in increased dopamine signaling, which manifests as the excessive movement characteristic of TD.1,16

TD and DIP show differences in the onset of symptoms16

- DIP usually develops within a few days or weeks of16,17

- Starting or increasing the dosage of an antipsychotic

- Reducing the dosage of a medication used to treat EPS (eg, anticholinergics)

- TD develops after using an antipsychotic for at least a few months17

- TD movements may appear after discontinuing, changing, or reducing the medication dosage; if symptoms persist for longer than 4 to 8 weeks, then the patient is considered to have TD. Older adults may develop TD symptoms in a shorter period of medication usage

Key features that differentiate TD from DIP include the nature and frequency of movements16,18

- TD is characterized by an excess of movements that are irregular, jerky, and unpredictable; TD movements are accompanied by normal muscular tone (Video 3)17-19

Patient images used with permission.

- DIP is characterized by a paucity of movement and, in some cases, rigidity. When movements occur, they are typically rhythmic (Video 4)15,18,20

Patient images used with permission.

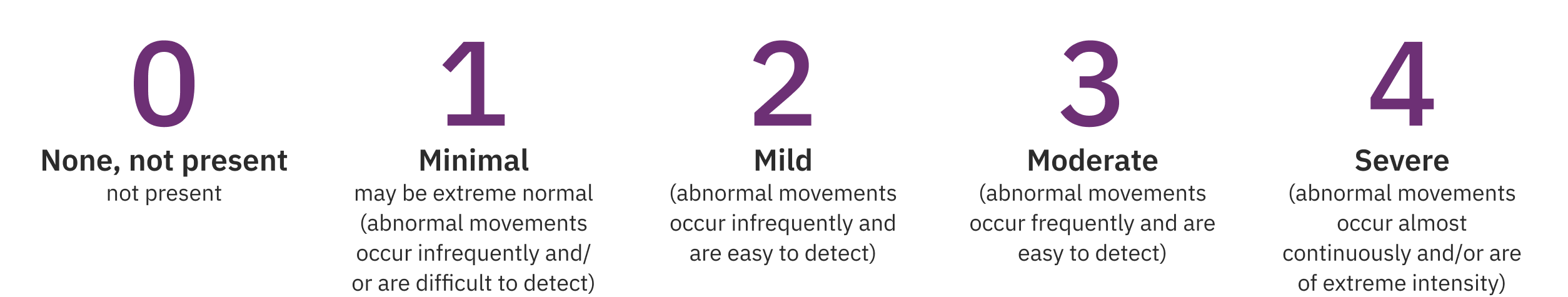

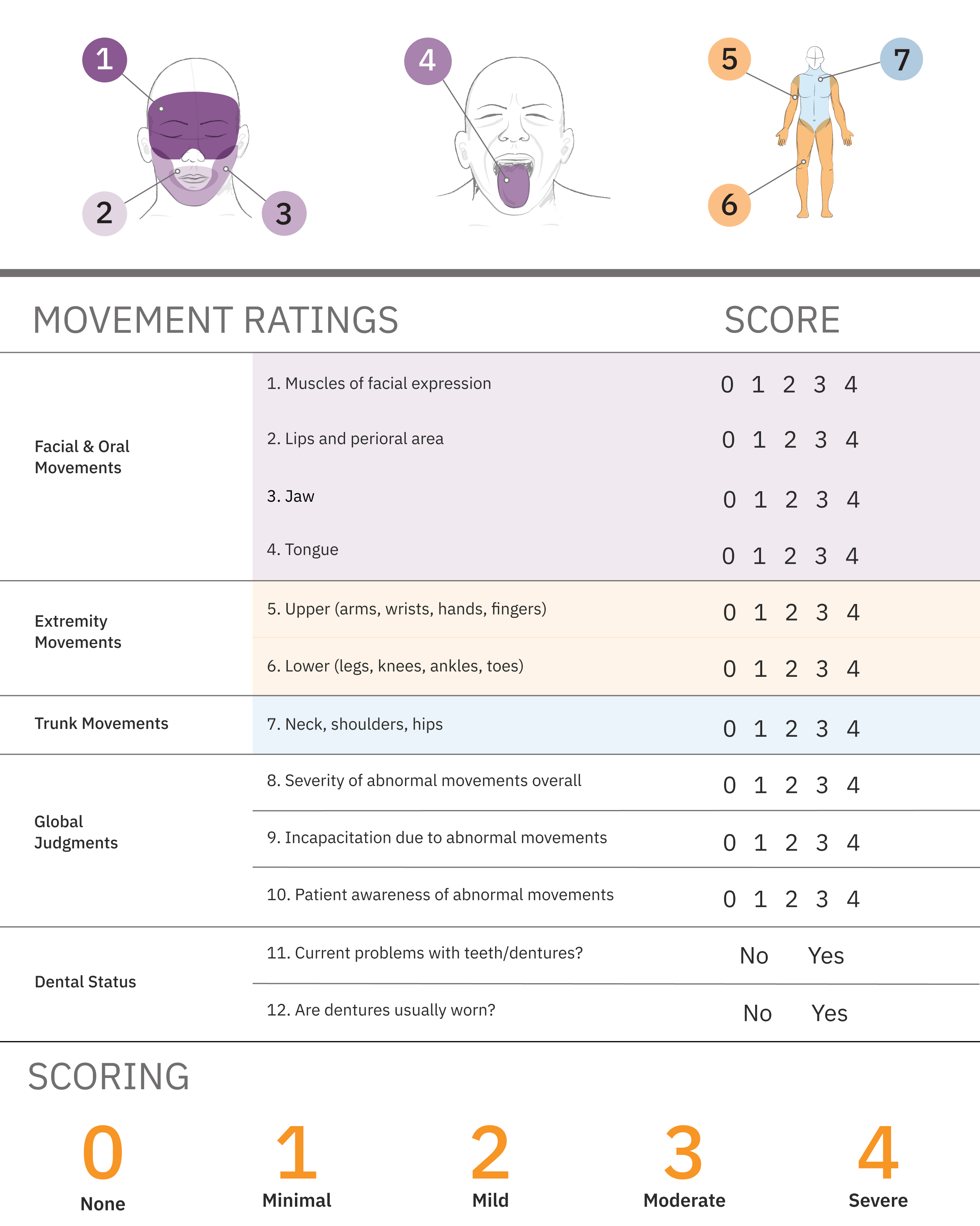

The AIMS is a structured exam widely used to screen for and monitor TD symptoms, consisting of 2 parallel processes3,9

- Following instructions to systematically observe and ask about movements in patients taking antipsychotics

- Scoring the severity of observed movements on a 12-item scorecard

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends all at-risk patients undergo an assessment with a structured instrument such as the AIMS and suggests patients at high risk be assessed at a minimum of every 6 months, while lower-risk patients should be assessed at least every 12 months. High-risk patients include individuals older than 55 years; women; individuals with a mood disorder, substance use disorder, intellectual disability, or central nervous system injury; individuals with high cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medications; and patients who experience acute dystonic reactions, clinically significant parkinsonism, or akathisia. Abnormal involuntary movements can also emerge or worsen with antipsychotic medication. Patients should also be assessed if a new onset or exacerbation of preexisting movements is detected at any visit.3

AIMS exam items 1 to 7 assess the severity of involuntary movements across body regions, while items 8 through 12 address global severity, patient awareness and distress, and dental issues. While AIMS items 9 and 10 quantify the impact of TD, determining the severity of impact requires further qualitative assessment.21,22

Each of the first 7 items is scored on a 0-to-4 scale23

The AIMS total score is the sum of items 1 to 7 and can range from 0 to 28 (Figure 1).

Ultimately, TD that impacts the patient, regardless of severity, should be treated with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, if it has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity of movements.3

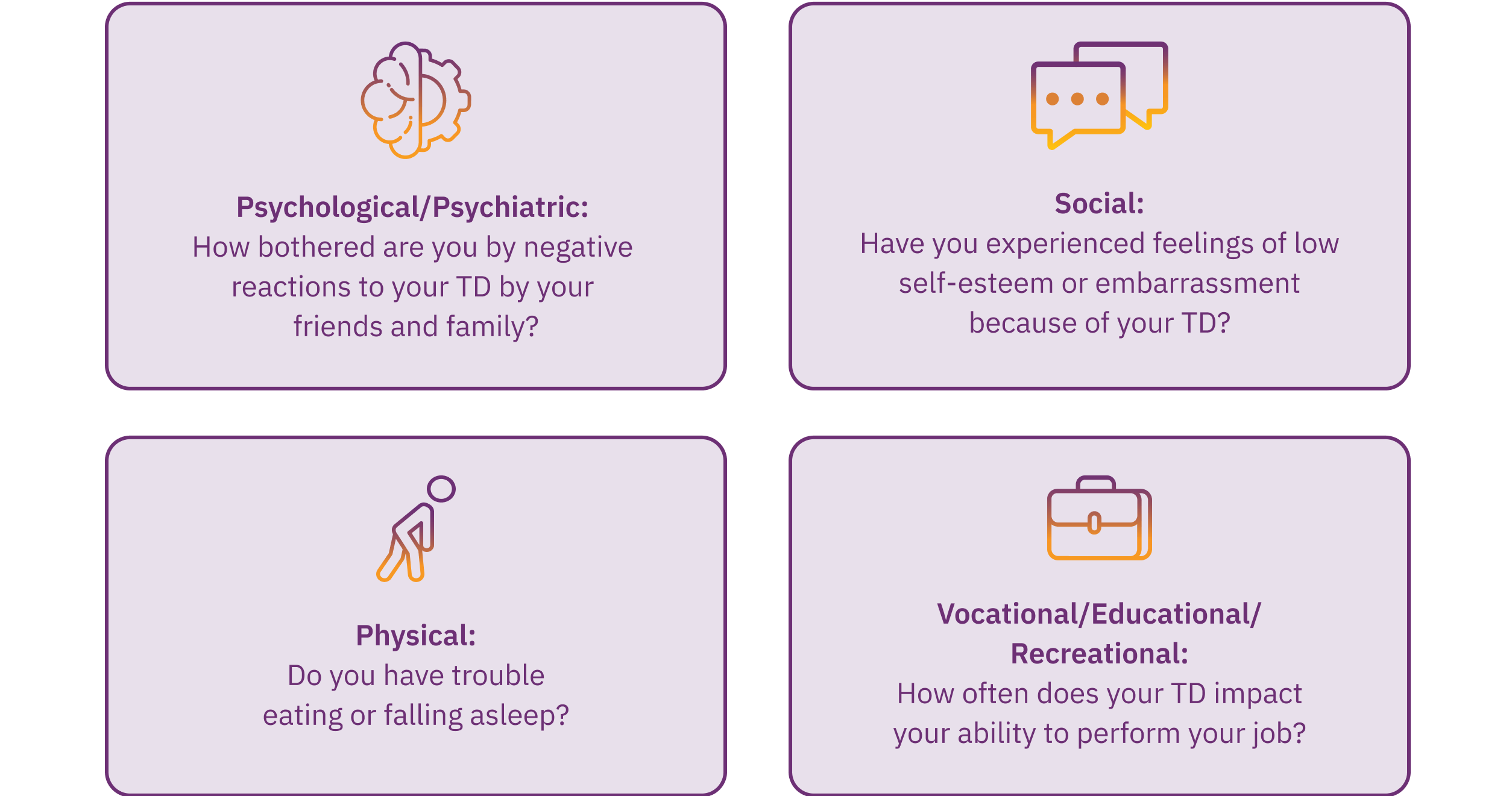

While the AIMS exam quantifies movements, the severity of TD can only be fully understood by considering the impact these movements have on the patients, regardless of their amplitude or frequency, in the various aspects of their daily lives. Therefore, it is crucial to ask appropriate questions and actively listen to your patients to grasp the impact of TD, particularly because clinicians may underestimate how TD movements, particularly those that are subtle, can impact patients’ lives.25 As a result, investigating the consequences of TD across 4 domains—psychological/psychiatric, social, physical, and vocational/educational/recreational—is essential. This can be achieved by asking questions to gauge the severity of the impact in each area (Figure 2).8,12 Receiving information from caregivers, family, and friends can also be helpful in determining the impact of TD on patients’ lives.8

Consider the IMPACT-TD Scale as a guide in clinical practice to assess the impact of TD. Click here to access.

The AIMS procedure contains elements that can also help clinicians identify DIP. These include1,23

Unobtrusive observance of the patient at rest and during activation maneuvers when the clinician may note rhythmic tremor

A close watch of the patient’s gait, during which the HCP might identify a lack of arm swing or shuffling of the feet, indicative of DIP

Assessing rigidity, which is an important component of the AIMS procedure, can help identify rigidity associated with DIP

Because DIP and TD may co-occur, testing for parkinsonian rigidity is an important corollary to the AIMS exam as rigidity may partially or completely mask dyskinesia.10

To further your knowledge and practice your scoring skills, please visit ConnecTD.

- All patients taking antipsychotics should be screened for TD movements at every clinical encounter, regardless of the risk of TD3,9

- TD and DIP have different causes1,15,16

- In DIP, acute dopamine receptor blockade reduces dopamine signaling, leading to decreased movement (ie, hypodopaminergic state)

- In TD, chronic dopamine receptor blockade results in upregulation of dopamine receptor function, leading to increased dopamine signaling and excessive movements (ie, hyperdopaminergic state)

- TD and DIP differ in symptom onset16

- DIP usually emerges within a few weeks to months of starting antipsychotic treatment16,17

- TD develops after using an antipsychotic for at least a few months17

- Anticholinergics are indicated for the treatment of DIP but can worsen TD symptoms16,17

- AIMS is a clinician-rated scale that helps quantify the degree of TD movements8,9,12,21-23

- Items 1 to 7 assess the severity of involuntary movements across body regions

- Items 9 and 10 quantify the impact of TD

- Determining the severity of impact requires further qualitative assessment by asking the appropriate questions and actively listening to your patients

- APA Guidelines recommend VMAT2 inhibitors, if TD has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity of movements3

- The AIMS procedure contains elements that can also help clinicians identify DIP1,23

1. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. 2. Caroff SN, Yeomans K, Lenderking WR, et al. RE-KINECT: a prospective study of the presence and healthcare burden of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice settings. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(3):259-268. 3. American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2021. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841 4. Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M, eds. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2011. 5. Zutshi D, Cloud LJ, Factor SA. Tardive syndromes are rarely reversible after discontinuing dopamine receptor blocking agents: experience from a university-based movement disorder clinic. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2014;4:266. 6. Stegmayer K, Walther S, van Harten P. Tardive dyskinesia associated with atypical antipsychotics: prevalence, mechanisms and management strategies. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):135-147. 7. Lee A, Kuo B. Metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2010;5(5):653-662. 8. Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. 9.Caroff SN, Citrome L, Meyer J, et al. A modified Delphi consensus study of the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19cs12983. 10. Munetz MR, Benjamin S. How to examine patients using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(11):1172-1177. 11. Isaacson, S. Personal communication; August 19, 2019. 12. Jackson R, Brams MN, Carlozzi NE, et al. Impact-Tardive Dyskinesia (Impact-TD) scale: a clinical tool to assess the impact of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;84(1):22cs14563. 13. Miller JJ. Everyone please stop (EPS). Psychiatric Times. 2022;39(8). Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/everyone-please-stop-eps- 14. Ogino S, Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Yamaguchi N. Benefits and limits of anticholinergic use in schizophrenia: focusing on its effect on cognitive function. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68(1):37-49. 15. Conn H, Jankovic J. Drug-induced parkinsonism: diagnosis and treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2024;23(12):1503-1513. 16. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia-key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248. 17. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2022. 18. Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Learning Network. June 15, 2021. Q&A: updates from Dr Rakesh Jain on managing tardive dyskinesia. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/psychbehav/qas/qa-updates-dr-rakesh-jain-managing-tardive-dyskinesia 19. Caroff SN. Overcoming barriers to effective management of tardive dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:785-794. 20. Patel T, Chang F. Practice recommendations for Parkinson's disease: assessment and management by community pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2015;148(3):142-149. 21. Lane RD, Glazer WM, Hansen TE, Berman WH, Kramer SI. Assessment of tardive dyskinesia using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(6):353-357. 22. STABLE National Coordinating Council Resource Toolkit Workgroup. STABLE Resource Toolkit. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/501791293/STABLE-Resource-Toolkit-Bipolar 23. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Revised. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976:534-537. DHEW publication number ADM 76-338. 24. OHSU. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). Accessed April 23, 2025.https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-10/%28AIMS%29%20Abnormal%20Involuntary%20Movement%20Scale.pdf 25. Finkbeiner S, Konings M, Henegar M, et al. Multidimensional impact of tardive dyskinesia: interim analysis of clinician-reported measures in the IMPACT-TD Registry. Presented at: Annual Psych Congress Elevate; May 30-June 2, 2024; Las Vegas, NV.